The goal of the package is to provide a flexible method of applying stability selection (Meinshausen and Buhlmann, 2010) with various model types, and the framework for triangulating the results for multiple models (Lima et al., 2021).

stabilise() performs stability selection on a range of

models to identify variables truly associated with an outcome.triangulate() identifies which variables are most

likely to be associated with an outcome across all models.stab_plot() allows visualisation of either

stabilise() or triangulate() outputs.simulate_data() allows the simulation of datasets to

facilitate user the comparison of various statistical methods.You can install this package from CRAN as follows:

install.packages("stabiliser")Or using the developmental version as follows:

devtools::install_github("roberthyde/stabiliser")The stabiliser_example is a simulated example dataset with 50 observations of the following variables:

yy:

causal1, causal2…y:

junk1, junk2…library(stabiliser)

data("stabiliser_example")stabilise()To attempt to identify which variables are truly “causal” in this

dataset using a selection stability approach, use the

stabilise() function as follows:

stable_enet <- stabilise(data = stabiliser_example,

outcome = "y")Access the stability (percentage of bootstrap resamples where a given variable was selected by a given model) results for elastic net as follows:

stable_enet$enet$stability

#> # A tibble: 100 x 7

#> variable mean_coefficient ci_lower ci_upper bootstrap_p stability stable

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

#> 1 causal1 2.58 0.207 5.45 0 90 *

#> 2 causal3 2.59 0.222 6.49 0 78.5 *

#> 3 causal2 2.12 0.0803 5.01 0 78 *

#> 4 junk14 2.58 0.0695 7.31 0 71 <NA>

#> 5 junk45 2.54 0.0526 5.76 0 63.5 <NA>

#> 6 junk13 2.55 0.136 6.07 0 60.5 <NA>

#> 7 junk88 1.88 0.0300 4.87 0 58 <NA>

#> 8 junk86 1.59 0.110 4.98 0 57 <NA>

#> 9 junk90 1.98 0.161 5.20 0 56 <NA>

#> 10 junk65 -1.25 -3.65 -0.0244 0 46.5 <NA>

#> # ... with 90 more rowsThis ranks the variables by stability, and displays the mean coefficients, 95% confidence interval and bootstrap p-value. It also displays whether the variable is deemed “stable”, in this case 3 out of the 4 truly causal variables are identified as “stable”, with no false positives.

By default, this implements an elastic net algorithm over a number of bootstrap resamples of the dataset (200 resamples for small datasets). The stability of each variable is then calculated as the proportion of bootstrap repeats where that variable is selected in the model.

stabilise() also permutes the outcome several times (10

by default for small datasets) and performs the same process on each

permuted dataset (20 bootstrap resamples for each by default).

This allows a permutation threshold to be calculated. Variables with a non-permuted stability % above this threshold are deemed “stable” as they were selected in a higher proportion of bootstrap resamples than in the permuted datasets, where we know there is no association between variables and the outcome.

The permutation threshold is available as follows:

stable_enet$enet$perm_thresh

#> [1] 74triangulate()Our confidence that a given variable is truly associated with a given outcome might be increased if it is identified in multiple model types.

Specify multiple model types (elastic net, mbic and mcp) for

comparison using the stabilise() function as follows:

stable_combi <- stabilise(data = stabiliser_example,

outcome = "y",

models = c("enet",

"mbic",

"mcp"))The stability of variables is available for all model types as before.

The stability results from these three models stored within

stable_combi can be combined using triangulate

as follows:

triangulated <- triangulate(stable_combi)

triangulated

#> $combi

#> $combi$stability

#> # A tibble: 100 x 4

#> variable stability bootstrap_p stable

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

#> 1 causal1 62.3 0.00292 *

#> 2 causal2 46.5 0 *

#> 3 causal3 45.3 0 *

#> 4 junk13 38 0 <NA>

#> 5 junk14 37.8 0 <NA>

#> 6 junk88 34.5 0 <NA>

#> 7 junk45 29.5 0 <NA>

#> 8 junk90 28.8 0 <NA>

#> 9 junk86 28 0.0204 <NA>

#> 10 junk65 19.8 0 <NA>

#> # ... with 90 more rows

#>

#> $combi$perm_thresh

#> [1] 43This shows variables consistently being identified as being stable across multiple model types, and consequently increasing our confidence that they are truly associated with the outcome.

Triangulating the results for stability selection across multiple

model types generally provides better performance at identifying truly

causal variables than single model approaches (Lima et al., 2021). As

shown in this example, the triangulated approach identifies 3 out of the

4 truly causal variables as being “stable”, and being highly likely to

be associated with the outcome y.

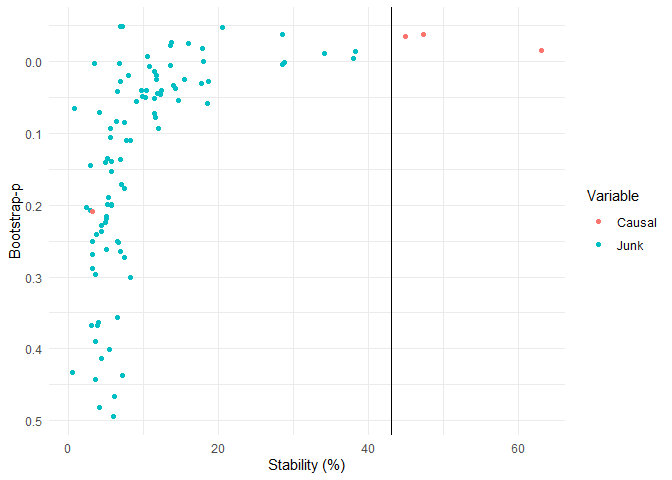

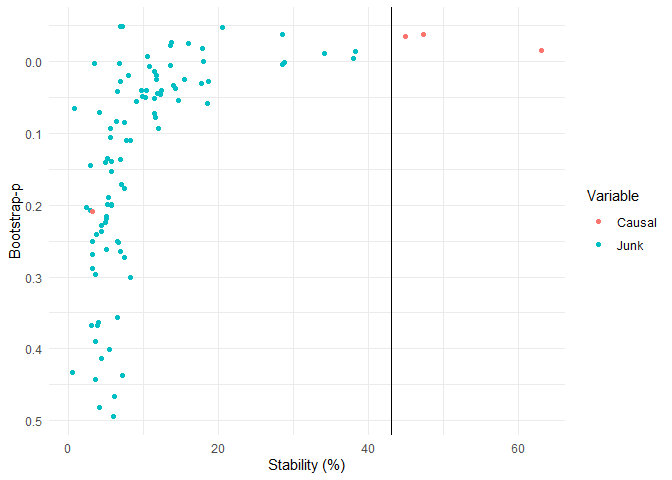

stab_plot()Both stabilise() and triangulate() outputs

can be plotted using stab_plot() as follows, with causal

and junk variables highlighted for this example:

stab_plot(stabiliser_object = triangulated)

simulate_data()To determine the optimum statistical approach, it can be useful to simulate datasets that are simular to those being explored within a research project, but with known outcomes.

The package includes a simulate_data() function, which

allows the user to simulate a dataset as follows:

nrows: the number of rows to simulate.ncols: The number of columns to simulate.n_true: The number of variables truly associated with

the outcome.amplitude: The strength of association between true

variables and the outcome.For example, simulating a 5 row dataset, with 5 explanatory variables, where 2 variables are truly associated with the outcome with a signal strength of 8 would be conducted using the code below. Note that the variables simulated to be truly associated with the outcome are labeled as “true_”, and variables that are randomly generated labeled as “junk_”.

simulate_data(nrows=5,

ncols=5,

n_true=2,

amplitude=8)

#> outcome junk_V1 true_V2 true_V3 junk_V4 junk_V5

#> 1 0.221365 -1.4714379 0.1265166 -0.2050986 -1.9603030 0.74586529

#> 2 -4.524082 0.8873447 -0.6569296 -0.4972537 1.0603469 1.03974907

#> 3 -3.948917 0.4930688 -0.4016229 -0.7191238 -0.7291698 -0.79151647

#> 4 -2.617451 -0.2217698 -0.6222874 -0.1586967 0.9645390 -0.03753633

#> 5 4.613613 0.1590784 -0.3425437 1.6222826 1.4840578 0.15464136It can also be interesting to simulate datasets with no variables

associated with the outcome (other than by chance). This can be done by

setting n_true to zero (or leaving to the default of

zero).

simulate_data(nrows=5,

ncols=5,

n_true=0)

#> outcome junk_V1 junk_V2 junk_V3 junk_V4 junk_V5

#> 1 2.2007843 -0.8401319 -1.52055028 -1.1568187 1.94737237 -0.12843586

#> 2 -0.1496611 0.7128174 0.50553131 0.8950869 0.02989857 -0.51574352

#> 3 -0.9676750 1.2115235 0.88489231 0.6895640 -0.39529438 -0.16517106

#> 4 0.3468111 1.3880437 -0.31587319 1.2727221 0.29985638 0.06233299

#> 5 -0.9533052 -1.0614021 0.09315892 -0.4079483 -0.17326474 -0.98466363By using simulated datasets with no signal other than by chance, it is possible to explore various modeling approaches to determine how many false positive variables might be selected with a given approach.

Lima, E., Hyde, R., Green, M., 2021. Model selection for inferential models with high dimensional data: synthesis and graphical representation of multiple techniques. Sci. Rep. 11, 412. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79317-8

Meinshausen, N., Buhlmann, P., 2010. Stability selection. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Statistical Methodol. 72, 417–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2010.00740.x